Optimisation and Risk in a World of Distributed Energy

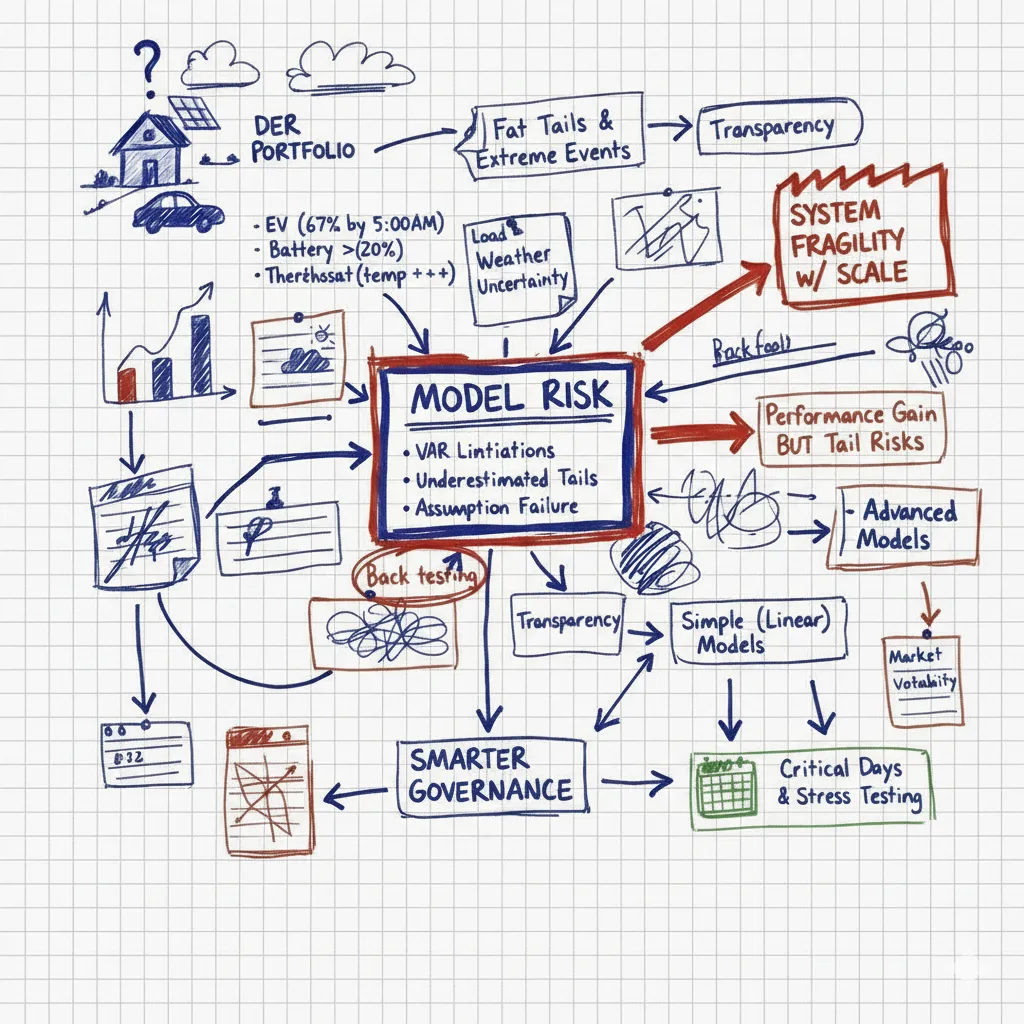

DER is scaling fast, and the risks are catching up. Software needs smarter optimisation and risk managers need to step up, or we will repeat the same mistakes finance made when models grew faster than governance.

Table of Contents

In a former life I worked in derivatives trading, hedging and risk management. It was a world where the physical thing behind a contract mattered less, and everything came down to exposure and how that exposure behaved when markets moved.

That mindset is becoming relevant in DER. Distributed energy is starting to resemble the early quantitative years of trading, where simple positions quietly turned into complex portfolios. The opportunity grows with scale, but so does the fragility. This is the right moment to look at how we optimise DERs today, what more advanced models are emerging and how we measure risk when those models meet real homes and real weather.

1. The Strengths and Limits of Linear Optimisation in DERs

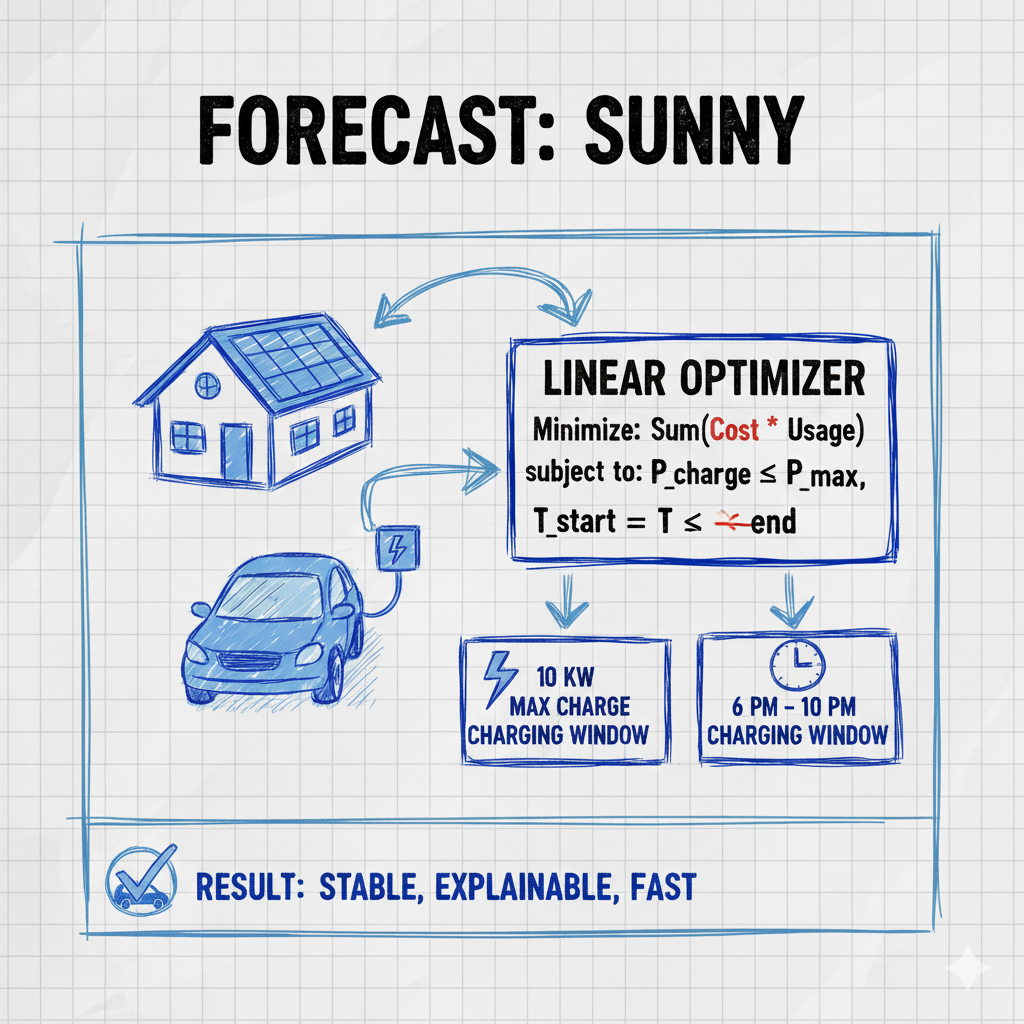

Most practical DER programs rely on linear or near-linear optimisation. These models define an objective such as reducing cost or avoiding a peak and solve within a set of device constraints. They are simple, fast and transparent. A battery has a power limit. A water heater has a recovery cycle. An EV has a charging window. Linear optimisation handles these structures well, which is why it remains common in operational energy systems.

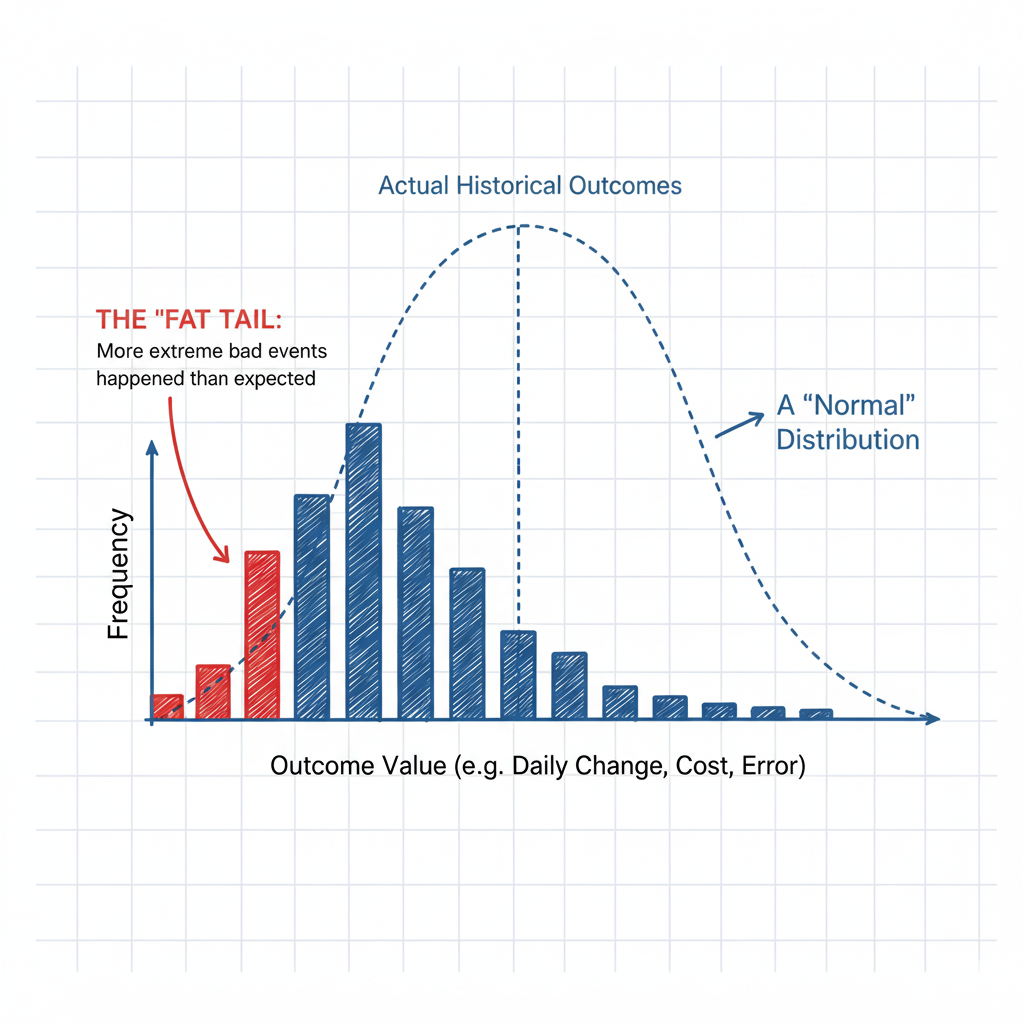

However, many programs simplify these formulations to the point where they behave more like structured rules than full optimisation. Large studies of power systems show that multi-asset interactions significantly influence load behaviour and that single-device optimisation often fails to capture system-level dynamics¹. Forecasts are frequently deterministic even though load, solar and price distributions display weather-driven variability and heavy tails².

This approach works on most days. It is stable, explainable and efficient. But when fleets scale or weather and behaviour deviate from the typical pattern, linear methods show their limits. Research in residential demand response finds that deterministic or simplified formulations degrade during cold snaps, atypical price patterns and overlapping device cycles³. Linear models give clarity but struggle to capture the complex, time-linked behaviour emerging in large residential fleets.

2. The Shift Toward More Advanced DER Optimisation Models

From simple equations to more expressive decision models

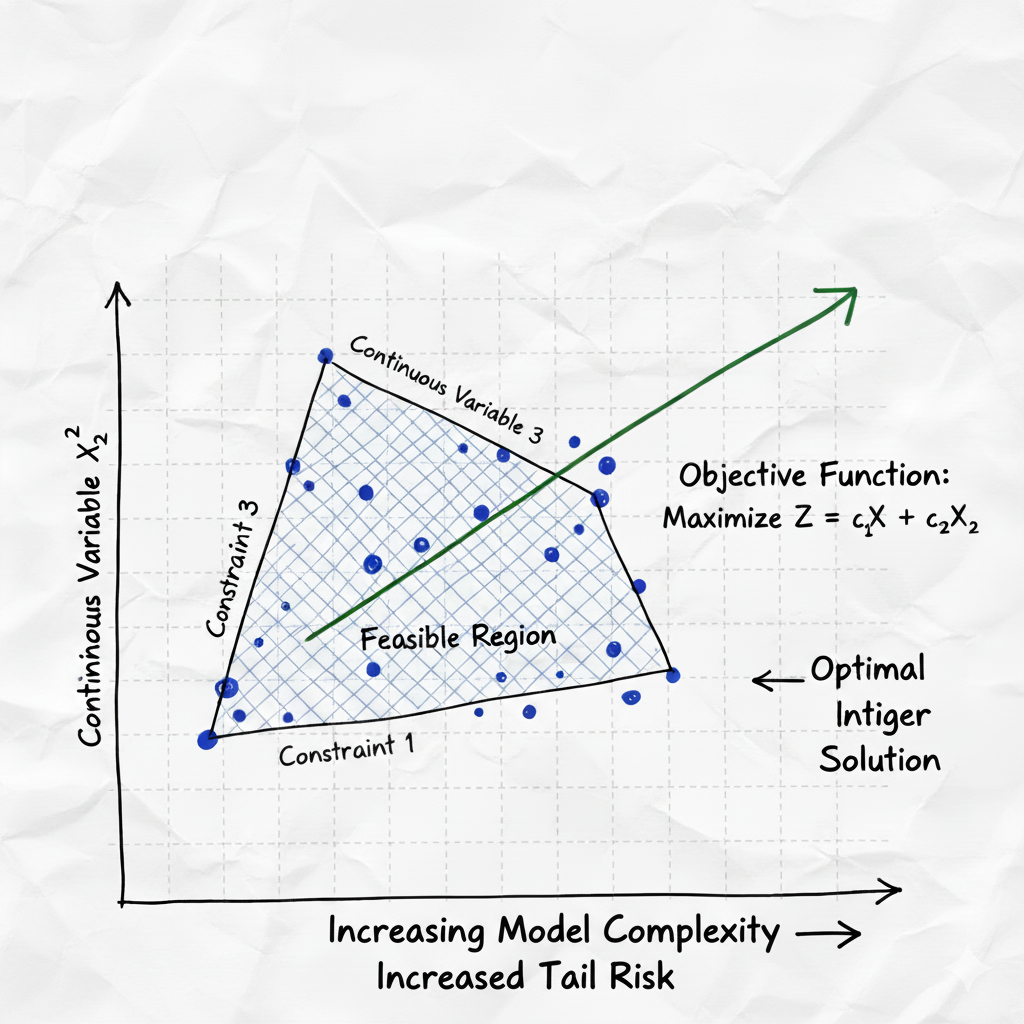

As fleets grow, the industry is shifting toward richer optimisation methods. Across the academic literature, stochastic optimisation, robust optimisation, mixed-integer programming, model predictive control and machine learning all demonstrate measurable advantages in uncertain or discrete environments.

Stochastic optimisation reduces volatility in outcomes and improves reliability under uncertainty¹. Robust optimisation strengthens performance against worst-case scenarios³. Mixed-integer formulations accurately represent discrete cycling patterns such as heat pumps and EV chargers³. Model predictive control adapts to new data by re-optimising on a rolling basis⁴. Machine learning and reinforcement learning models capture non-linear interactions that are difficult to encode manually⁵.

The trade-off: performance gains and rising complexity

The trade-off is complexity. More expressive models introduce more assumptions, greater computational demand and more ways for rare events to break the model. Reviews in finance and energy engineering show that models with many degrees of freedom can be sensitive to calibration windows and tail events⁶. Sophisticated techniques perform well most of the year, yet become less predictable when conditions move outside the model’s expected range.

For DERs in homes, this matters. Better optimisation can improve comfort, savings and grid support most of the year, but a single poorly handled extreme event can undermine trust. More intelligence improves average performance but increases the importance of understanding how the model behaves at the edges.

3. Tail Risk and the Limits of Complex Optimisation Models

Why complex models often struggle in unusual conditions

Experience from quantitative finance shows that complexity raises tail risk when assumptions fail. When correlations shift or behaviour moves outside the model’s training range, outcomes can diverge sharply. Risk metrics such as Value at Risk help quantify downside but have structural limitations. VaR underestimates losses in the tail because it measures a threshold rather than the magnitude of losses beyond it⁶. During the 2007 to 2009 crisis, VaR models produced multiple exceedances as volatility regimes shifted⁷.

Proof in the data: why governance matters as much as the model

There are clear cases where model implementation errors understated exposure. In the J. P. Morgan London Whale incident, a spreadsheet formula in the bank’s VaR calculation used a sum instead of an average, materially understating risk⁸. Long-Term Capital Management relied heavily on the stability of historical relationships; when several rare events clustered, its assumptions failed⁹.

These cases do not imply that advanced models are unsafe. They show that advanced models without governance are unsafe. The same applies to DER. Optimisers that behave perfectly during normal days can fail during cold snaps, hea

4. Why Smarter Optimisation Requires Smarter Governance

Advanced optimisation is essential for scaling DER. It improves comfort, savings and grid resilience. But it also increases the need for stress testing, scenario analysis, backtesting and transparency. Tail behaviour does not improve simply because models become smarter. It improves when models are monitored, challenged and governed with the same discipline that quantitative industries have learned through experience.

Working alongside risk managers in financial institutions meant every optimisation method faced scrutiny. Assumptions were challenged. Stress scenarios were mandatory. DER is now approaching that same tipping point. The next phase of growth is not only about smarter optimisation. It is about smarter oversight.

References

- ¹ Roald, L. et al. Power Systems Optimization Under Uncertainty: A Review of Methods and Applications. PSCC 2022. https://pscc-central.epfl.ch/repo/papers/2022/22730.pdf

² Zhou, Z. et al. Stochastic Methods Applied to Power Systems Operations with Renewable Energy. FERC. https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/T1-A-1-ZHOU.pdf

³ Parisio, A. et al. Robust Optimization of Operations in Energy Hubs. https://www.researchgate.net/.../Robust-Optimization-of-operations-in-energy-hub.pdf

⁴ Model predictive control principles applied to microgrids in Zhou et al., FERC (above).

⁵ NREL. Machine Learning for Distributed Energy Resources. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/75555.pdf

⁶ Bank for International Settlements. Fundamental Review of the Trading Book. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d352.pdf

⁷ Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Why VaR Failed the Financial System. https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/el2011-18.pdf

⁸ SEC. JPMorgan London Whale: Administrative Order. https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2013/34-70694.pdf

⁹ International Monetary Fund. The Rise and Fall of LTCM. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2000/wp0034.pdf